Design process

How BDM is being developed

Here we discuss the guiding principles and how they are applied to the development of the BDM.

BDM is similar to the domain-specific data models used in various domains, specifically designed to address the unique diversity of data in cognitive and behavioral sciences. The development of BDM is an iterative process guided by two design patterns: Domain-Driven Design and Data Lakehouse.

Domain-Driven Design aims to develop a shared understanding of data that works for both domain experts and technical experts.

And Data Lakehouse helps with harmonizing a diverse se of data without sacrificing flexibility or speed (cognitive data can be thought as multi-modal, even at the level of tasks).

These two patterns address the shortcomings of metadata-centric methods, which are often costly and ineffective at achieving reusability 1,2, and emphasize the need for a shift from ad-hoc metadata to robust data structures. They encourage a ubiquitous language for many cognitive tasks, crucial for developing tools and fostering collaboration in research.

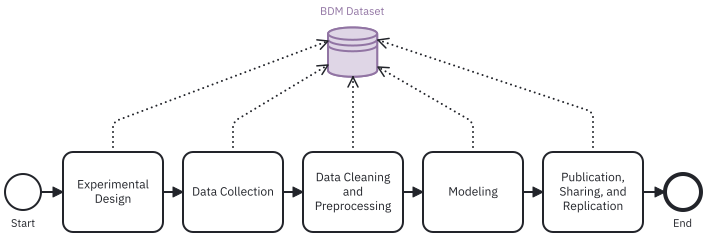

Moreover, BDM aims to address data management during all the steps of a research workflow, from the start to its completion:

Domain-Driven Design

Behavioral data is inherently complex due to the variety of data types, the diversity of experimental designs, and the need for precise data interpretation. Traditional data management approaches often struggle with the variability and context-dependence of behavioral data. Such domain-specific complexity are best addressed in software engineering by Domain-Driven Design (DDD), which is a structured approach that aligns technical design with the specific needs of the domain, which in our case is behavioral science.

One of the primary benefits of applying DDD to behavioral data is that it serves as the foundation for all study design, data collection, pre-processing, and analysis phases. It also ensures consistency across different studies while accommodating the unique aspects of different experiments. DDD’s focus on bounded contexts allows for the clear definition of key concepts like “Trial,” ensuring that these concepts are used consistently across different settings.

Unlike rigid standards, flexibility of DDD allows for cost-effective and optional opt-in for some of its features. Ontologies and standards that are purely based on domain knowledge often lead to unstructured, raw knowledge. DDD, on the other hand, addresses the need for developing tools to conduct research, and provides a language that bridges the gap between domain experts and technical experts.

Events

Most of the time, raw data can be modeled as a series of events. Events are discrete occurrences that capture specific actions or changes in state during a cognitive task. Examples of events include the presentation of a stimulus, the recording a response, or the selection of an option.

Events are often recorded as soon as they occur in a transactional way, meaning that they are resulted from an interaction between the task and the agent. This data structure is more convenient for the software than storing complex data structures (like trials), as most code is written to control user interactions and store the corresponding data.

Trials

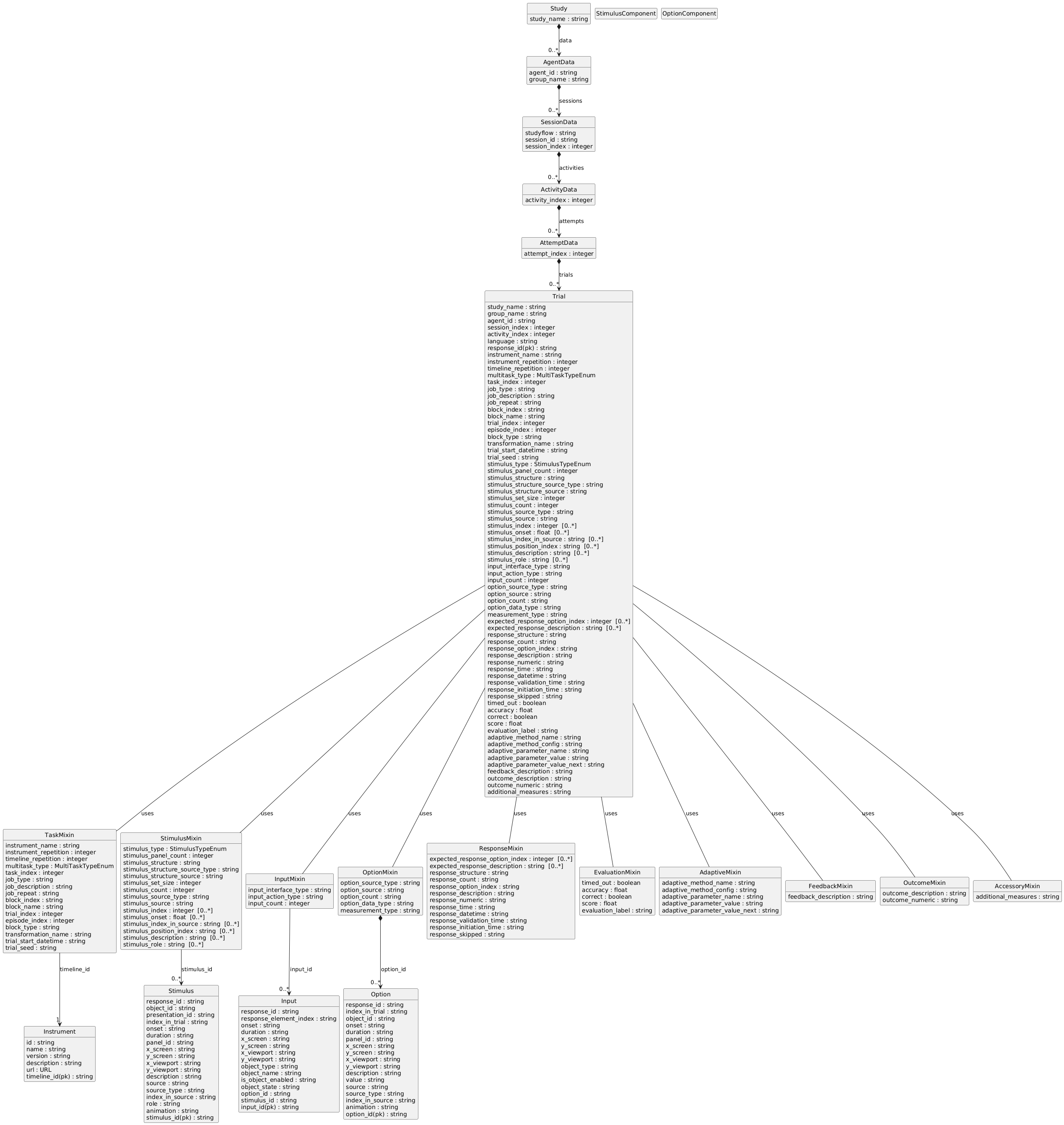

Trial is the main aggregate root of a BDM dataset. It represents a single meaningful instance of an agent performing a task, derived from all the events occurred during that instance.

A trial includes various components: Responses, Stimuli, Options, Outcomes, Evaluation, etc. These components are essential for understanding the context and results of a trial. Together, they represent the meaningful unit of analysis for researchers.

Projections

Trials are built from events using projections. They are semantic layers on top of the events and define how events are interpreted and gathered into a trial. Projections are task-specific and can vary based on the experimental design.

In a more technical sense, projections are like views in SQL which aggregate normalized rows (i.e., events) into a queryable summary (i.e., trials). This keeps the events as the only source of truth while providing trials that are optimized for domain-specific analysis.

Other domain concepts

Core domain concepts:

- Response

- Stimulus

- Option

Supporting domain concepts:

- Agent

- Task (task-specific projection that defines how events are aggregated into trials)

- Experimental design (e.g., studyflow, adaptive parameters, conditions, etc)

- Instruments (i.e., the environment in which the task is performed)

Here is a diagram of the trial. The diagram shows the relationships between the domain-specific concepts and their attributes.

Data Lakehouse

A missing but important aspect in behavioral datasets is how to make analysis of data easy, cost-effective, and consistent while keeping the harmonizing/federation of data straightforward. For this reason, BDM relies on data lakehouse architecture which, unlike previous approaches, provides a lost-cost ingestion/storage/consumption based on a schema-on-read. Lakehouse allows, during study design and data collection, to only focus on the ubiquitous language of trials and events and later one, during the analysis and modeling, to apply loosely-coupled techniques to standardize datasets.

Overall, considering events and trials as the ubiquitous domain concepts and data lakehouse as the harmonization approach make it possible to scale and manage behavioral analysis systems. New challenges involve storage, debugging, increased traffic, and extending the data architecture to new tasks and modalities.

Data partitioning

Identical data structure

Levels of data

Behavioral experiments require and produce a variety of interrelated data, from instructions shown to the subjects, task parameters, and recorded interactions, to aggregated trials data that are interpretable in accord with the scientific question. If we consider cognitive tasks as a set of interactions that participants do, trial only captures the final state of those interactions. Events on the other hand allow us to reconstruct the history of interactions. However, events are not commonly used during the analysis and most researchers are only interested in the final states of events, i.e., trials.

For software engineers however, it’s more convenient to collect transactional events rather than waiting for some final states; most codes are written as controlling some user interactions and storing the corresponding data. Trial data is an implicit post-processing of those event data. For a full reconstruction of what happened during the task, events data is more useful and it also leads to datasets that can be used in more modern disciplines such as RL where we are interested in learning how an agent interacts with the environment, rather than the final decisions.

Data governance

- Versioning

- Metadata

- MLOps

Footnotes

N. Sambasivan, S. Kapania, H. Highfill, D. Akrong, P. Paritosh, and L. M. Aroyo, “Everyone wants to do the model work, not the data work: Data Cascades in High-Stakes AI,” in Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI’21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, May 2021. doi: 10.1145/3411764.3445518.↩︎

M. Hulsebos, W. Lin, S. Shankar, and A. Parameswaran, “It Took Longer than I was Expecting: Why is Dataset Search Still so Hard?,” in Proceedings of the 2024 Workshop on Human-In-the-Loop Data Analytics, in HILDA 24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, June 2024. doi: 10.1145/3665939.3665959.↩︎